I’ve never been as consistent with my blog game as I’d like. I do plan to update this site with links to talks, articles, and events… just not now. If you are curious about what I am working on Twitter is a good place to start: @lizdubois. You can also contact me.

How did Trump win? (or, the bias of our political information)

Trump broke the mould which makes it difficult for political scientists and strategists alike to understand the dynamics of his win. But conveniently, when we say “how did he win?” we actually mean, “how did I miss this?” This is a question we are much better equipped to answer.

tl;dr: You missed the whole “Trump is actually popular” thing because you prefer not to see a world where he is. And, your social media is helping you do it.

(A quick note on evidence, I am linking to various academic sources where you can find more about the theories and arguments I am summarizing. These are a starting point. Feel free to leave a comment with additional sources.)

Preferences and Personal Choice

There is a lot of information out there and not a lot of time in the day to access it all. We humans have to choose what we pay attention to and what we ignore. We prefer things that feel comfortable, that fit with our existing ideas about the world and that reassure us that we are on the right track. If we like news we seek out more of it, if we don’t we binge Netflix (among other things).

Source: There are a bunch of people from psychology to media studies arguing these points, Prior’s work is a good place to start.

Homophily, When Birds of a Feather Flock Together

Not only do we like information and ideas that already fit into our belief system, we also like people who are similar to us. We tend to spend more time with people from a similar background, who work in the same kinds of jobs and who have a similar socio-economic status. The term to describe this phenomenon is homophily and we see it everywhere from who we hang out with on the weekends to who we chat with on Twitter. So, even when we care about politics we tend to only be exposed to people similar to us and ideas similar to our own.

Source: McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook do a great job of outlining homophily.

The Spiral of Silence

Even when we do find our way into communities and conversations that take a view that is different from our own, we usually do not decide to contribute. When we believe the dominant view is different from our own we normally avoid giving our opinions for fear of social repercussions. This was observed in a mass media era and more recently in the context of social media and online social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter. Trump supporters just aren’t going to out themselves to communities of people enthusiastically saying #ImWithHer.

Source: Noelle-Neumann initially described the Spiral of Silence which became a fundamental theory in media studies research. Hampton and colleagues at the Pew Research Centre tested the theory in the context of social media.

Opinion Leaders, That Super Engaged Friend

To make matters worse, we normally get a lot of our political information from friends and family and our political opinions are often formed, at least in part, through discussion with people we personally trust. We call these people opinion leaders and they are normally people who are very similar to us but who happen to be a little more interested in political news. This process was first called the two-step flow.

As if it were not enough to be getting information from people who are primarily just like us, these opinion leaders are also making strategic use of their channels of communication in order to avoid social conflict. If we are worried we might make our friends angry we are less likely to post political content to Facebook. This leads people to self-censor.

Source: The two-step flow was first articulated by Katz and Lazarsfeld, here is a good breakdown of that early theory. It has been modified and questioned a bunch over the years but the notion of the opinion leader being a crucial player (see Norris and Curtice, for example). Finally, my own doctoral work focused on the self-censorship on social media aspect.

Gatekeepers

But before we even get to the point of picking content we prefer or hearing about issues from friends based on what they think we will prefer, the mainstream media play a crucial role. For example, the mainstream media (where most of us get the majority of our political news) picks which stories to report on and what angle to present. They both filter information (serving as a gatekeeper) and tell us what to think about (serving an agenda-setting function). Even when we read news from respected media sources we get a particular perspective — one we selected based on things like our existing preferences, what we have come in contact with before, and what our friends consult and trust.

Sources: Both gatekeeping theory and agenda-setting theory are fundamental notions in political communication, media studies and journalism research. There are many books and articles but I actually think their respective Wikipedia articles are the best place to start.

Filter Bubbles and Algorithms

Last but certainly not least, most of us get some if not the majority of our political information through social media and online search. The problem is, Facebook and Google are designed to give us more of what we want and less of what we are likely to find annoying, boring, threatening, etc. We see more from people who’s posts we have recently “liked,” and news websites from our local area get pushed to the top of search results. Don’t get me wrong, these are wonderful features in many ways but it does mean that we can end up in personalized little bubbles. We end up being served more of what we already “like” and “share” and that can make us think our preferences are actually everyone’s preferences.

Source: Pariser describes the filter bubble in his book and this TED talk.

So, quick summary:

You missed the whole “Trump is actually popular” thing because you prefer not to see a world where he is. And, your social media is helping you do it. You prefer a certain amount and certain kind of news that means you were exposed to things that confirm your existing beliefs and preferences about the election (#ImWithHer #WhoWouldntBe #Duh). Most of the people around you are just like you and so you reinforce each other’s views (you nasty woman, you) and inadvertently, or maybe intentionally, push away anyone who disagrees. Even your super engaged political friends who are more likely to be exposed to lots of different views (because they go out of their way to find them since they prefer it that way) are unlikely to share divergent opinions and likely self-censored this election in certain contexts. News media are filtering information based on what they think is most relevant to society and Facebook and Google are filtering information based on what they think is most relevant to you.

We’ve got all kinds of layers helping us sift through the masses of information out there and that is not only inevitable but also useful. The trick is we need to be careful about how we use them or, you know, let them become so ubiquitous we don’t even know they are being used.

Canada’s Open Dialogue Community #CODf16

Top thinkers (and doers) in Canada’s #opengov (open government) space are meeting in Ottawa for the Open Dialogue Forum March 31st and April 1st, 2016. Not surprisingly, given the audience, the Twitter chat was on point. I’ve done a quick analysis of the mention network from the #CODF16 tag in order to map out who is talking and who is being heard.

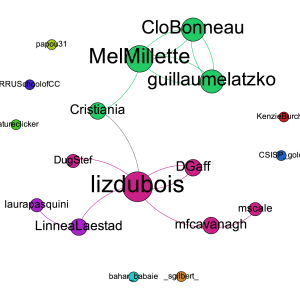

The network:

For those not familiar with network graphs, the dots represent Twitter accounts and lines represent when one account mentions another. In network science those dots are called nodes and lines are called edges.

This graph shows everyone who made a tweet using the #CODF16 hashtag on March 31, 2016. The colours represent clusters of account who tend to mention each other. The nodes are bigger the more times someone else mentioned them. Obviously this graph is pretty messy and hard to understand so lets break it down.

Top level (the tl;dr you busy folks):

- There is one major community of accounts chatting but sub-communities (“clusters”) exist.

- There are no clear divides based on type of stakeholder which means conversation is happening among different kinds of actors (a key goal of the forum).

- There is an imbalance in who mentions and who gets mentioned which probably means the Twitter conversation is not reaching all types of stakeholders (notably, politicians and journalists seem to be largely absent from discussion).

I’ll talk to you, blue:

The biggest cluster of accounts is light blue. That big node in the middle is@CdnOpenDialogue (the event’s official account). I know, what a surprise, the ones who organize it are mentioned a bunch. In fact that account was mentioned 118 times (they mentioned others 65 times).

But, there is another account that was mentioned even more: MP Scott Brison. He got 130 mentions while only sending out 2 himself. He is in the dark blue cluster:

Where the conversation is happening:

These two examples are pretty typical of Twitter chat. We see accounts with some type of popularity have high “indegree centrality” — that means they are mentioned a lot. But, what about those doing the mentioning? They are normally the ones asking questions, responding to comments and sharing different ideas. We can find them by looking for “outdegree centrality” — those who mention a lot.

Let’s look at that first cluster again:

We’ve still got the organizers but now another node pops up.@DoreySamson was mentioned 14 times but made 64 mentions.

Similarly, in another cluster Canada 2020 (on Twitter) pops up:

And, you guessed it, @ScottBrison is no longer particularly central, but others around him are:

When you dig deeper into the clusters you see a lot of different kinds of stakeholders in each one. Think tanks, government officials, academics etc. are all communicating with each others. That said, those who are most engaged in back and forth communication tend not to be the organizers or politicians.

A word about words:

I can’t do the content justice in this quick post so I won’t provide analysis of what people are saying at this point. But I do want to share a few quick things:

- “Open” is the most frequently used word in the dataset.

- #OpenGov is the hashtag most often used along side #codf16.

- There were 2894 tweets made by 497 unique accounts at the time of analysis.

What it means:

Open Dialogue Forum has so far succeeded in generating chat among a variety of stakeholders. For the most part these various types of stakeholders are engaging with each other. Notably, there are not many journalists engaged in this network which is pretty abnormal for any kind of political chat in the Canadian Twittersphere.

I haven’t been studying this community over time so I can’t say if the forum was the cause of these connections but I can say that it has done a good job of sparking conversation.

What’s your thesis again?

Having recently completed my doctoral work a common question is “what is your thesis actually about again?” Well, here it is.

In my thesis (link) I look at the idea of the opinion leader – an average citizen who happens to care a lot about politics and pays attention to current affairs. In communication theory we assume opinion leaders act as a bridge between the political elite (think politicians and journalists) and the general public who don’t pay very close attention to what is going on politically. What I find is that digitally enabled opinion leaders actually work very hard to use their channels of communication to avoid anyone who is not already politically engaged. Digitally enabled opinion leaders (the one’s I interviewed at least) don’t like to be the bridge.

Let’s take a beat to unpack this.

Who cares if opinion leaders are or are not acting as a bridge?

You do! We know that there is a widening gap between the politically aware and unaware (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). We know people use digital channels of communication to avoid information they dislike or are not interested in (Prior, 2007). And we know that when people are not aware policy making becomes less responsive to citizen’s needs (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996) and people feel disconnected from their political system (OECD, 2011). In other words, democracy stops working (Dahl, 2000).

What makes any of this interesting or relevant now?

We’ve got a bunch of new channels of communication available to us – that’s all of us, elite, opinion leader or average Joe who hears JT and thinks Timberlake but not Trudeau.

More channels means more opportunities for sharing information and opinion. It also sometimes means new approaches to communicating politically (just think about citizen journalism or hashtag campaigns.) When it comes to opinion leaders, we don’t have a grasp on what channels of communication they are using, how or with what impact. I am talking about Facebook and Twitter sure, but even text messaging and email still need to be included.

Note: I base my work in the context of what Chadwick calls the hybrid media system (2013). Basically, Chadwick explains that lots of different political players have access to lots of different (and often overlapping) tools and tactics of communication. Opinion leaders are one kind of political player.

Fine, but why do these new channels impact the role of the opinion leader?

A lot of people have studied how opinion leaders go about informing the general public and it comes down to personal influence (see Katz, 1957 for an initial review). They use social pressure and social support to change the opinions, attitudes and behaviours of their everyday associates. This is normally done via face-to-face interpersonal communication since other options like broadcast are out of the question (a printing press has a rather large price tag).

But, you say, social media is cheap. Email is cheap. You’re right. New technologies throw the whole theory into question because we don’t actually know what opinion leadership looks like once we’ve got new channels.

What we do know is that these channels of communication open the door for accessing wide segments of the population via interpersonal (emails with mom), impersonal (broadcasting) and quasi-personal (mentioning someone on Twitter) communication.

The thing is, we used to assume that opinion leadership works because opinion leaders have a special social tie to the people who they influence. They know them well and interact with them regularly. There are a bunch of social influence theories that help us understand why we are more likely to be influenced by people who are like us and people who we spend a lot of time with – wanting to be a cool kid, for example, is pretty hardwired in our brains.

We also know that the most new information comes from people with whom we have only a weak tie, like the colleague from another city you only see in person during the annual staff retreat or the man who sells you veggies at the market (Grannovetter, 1973). That is because of a social phenomenon called homophily which basically means we surround ourselves by people like us – you know, birds of a feather flock together (McPhersen, Smith-Lovin, Cook, 2001).

So, where do people who are not interested in politics get political information from? Possibly weak ties. What information is likely to change the opinion of someone whose closest friends all think like them? Probably information from weak ties.

I’m lost, don’t you study social media?

Yup. Here it is, social media allow us to access and maintain close personal ties in new ways. Social media also allow us to access new ties and connect with people who have very diverse experiences, opinion and access to information. I wanted to know the impact of those channels (and other digital media) on the role of the opinion leader. When they talk about politics are they still able to be a bridge when they don’t have to rely on face-to-face communication? Is their influence greater because they can reach a lot more weak ties or is it limited because they try to communicate in a way that doesn’t let them capitalize on their social placement (it would be like the cool kid going to a new school and seeing if anyone starts to dress like them).

So, what do digitally enabled opinion leaders do?

Well, they make use of a lot of channels of communication for accessing information. Importantly this consistently includes accessing at least some mainstream media on a daily basis (from following them on Twitter to subscribing to the online version to turning on the radio).

When it comes to sharing information two distinct strategic approaches emerge. Some opinion leaders, who I call enthusiasts surround themselves with others who are equally passionate about politics. They use channels like Twitter and discussion boards to hone their arguments and to get a sense of what people with conflicting opinions think. It is something of an echo chamber of the politically engaged. On the other hand there are champions who act much the same except in situations of heightened political tension like a scandal or an election. Then these champions take it upon themselves to use every channel and tactic of communication they can to try and inform and influence people who are uninformed. They borrow the strategy of communications professionals and political elite to get their message across when they think it matters most.

Both enthusiasts and champions are trying to avoid the social risk of talking about politics with someone who won’t care.

What does this mean?

- Digital channels of communication are enabling a highly strategic opinion leader.

- Personal influence is not necessarily tied to interpersonal communication and so we need to think about the different types of influence these opinion leaders employ.

- Digitally enabled opinion leadership today is contributing to a much wider phenomenon where the vast majority of the public only become informed of political issues at moments of heightened tension (what I’ve been calling a just-in-time informed citizenry).

Communication theory and strategy both need to be responsive to these shifts.

A note on methods.

I am quite the methods geek which means a big part of my doctoral work was figuring out the best way to measure these things. I collected about 411 000 #CDNpoli tweets and created a friendship network of the users. Next, I conducted an online survey among #CDNpoli users. Finally, I did an in depth analysis of the communication practices of 21 opinion leaders from that network and 26 of their associates through interviews and analysis of Twitter and Facebook activities. There are obviously a lot of advantages and disadvantages to this mixed-methods approach so if you want to know more I am happy to chat. I’ve also published two journal articles on my methods and am happy to send you a copy of my thesis if you want to tackle the 336 page PDF.

Research questions.

In case you are interested,

RQ1 What are the modes of access to and dissemination of political messages by digitally enabled opinion leaders?

RQ2 What drives channel choice among digitally enabled opinion leaders when disseminating political information?

This question is broken down into six sub-questions (in my theory chapter I connect each to a specific body of existing research beyond the broader bodies of work noted above):

- RQ2.1 How does the richness/leanness of media channels influence digitally enabled opinion leaders’ channel choice?

- RQ2.2 How does the social appropriateness of exchanging political messages (given a particular channel) influence digitally enabled opinion leaders’ channel choices?

- RQ2.3 How does the political climate influence digitally enabled opinion leaders’ channel choices?

- RQ2.4 How does one’s sense of community (given a particular channel) influence digitally enabled opinion leaders’ channel choices?

- RQ2.5 How does the strength of social ties to their audience influence digitally enabled opinion leaders’ channel choices?

- RQ2.6 How does knowledge about one’s audience influence digitally enabled opinion leaders’ channel choices?

RQ3 What are the impacts of the channel choices made by opinion leaders on their political role?

References:

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

- Dahl, R. A. (2000). On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans don’t know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78 (6), pp. 1360–1380.

- Katz, E. (1957, March). The two-step flow of communication: An up-to date report on an hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21 (1), 61–78.

- OECD. (2011). Civic engagement and governance (How’s Life?: Measuring Wellbeing). OECD Publishing.

New job, new city.

Well, it is done. The thesis is defended (successfully) and I have hit the academic job market and come out with surprising speed. I am pleased to say that in January 2016 I started a job as an Assistant Professor at the University of Ottawa. My focus will be on international communication and digital media. I am pretty excited to be back in Ottawa where I actually completed my undergraduate studies in the very same Communications Department that I am now a working in.

As for the blog and my research updates. They will be getting back on track now that I’ve landed in a new role.

Stay tuned.

Research Update 5: Sprint, sprint, submit.

When do you plan to hand in? That evil question every doctoral candidate is peppered with pretty much from day one. You fumble around and propose a date. Even the most determined candidates are only guessing. The date is years away but slowly it creeps up.

You submit a chapter at a time and you present pieces of your work here and there. Eventually it is time to string it together. If you are like me, this is a pretty invigorating but all-consuming process. I worked in three four day chunks bringing things together and writing an introduction and conclusion (the first of which would be re-written and the second scrapped entirely). Those days were long and lonely.

I submitted and sat at my desk. I had stacks of cereal bowls and days worth of water glasses. I was in my pyjamas and had not been outside save to buy lunch from Whole Foods each day (the extra 5 minutes to the student friendly priced grocery store was just too valuable). I had expected to be elated that a full draft had been submitted but I was anxious instead. I still can’t pin-point why, but my stomach was in a knot and I pretty much just wanted to curl in bed and cry. Instead I took a shower. Then I curled up in bed.

A few weeks later comments were back from my two supervisors and it was time for sprint 2. Head down and off I went. This time I was also launching a non-profit organization aimed at increasing youth voter turnout. My days were as long but a little less lonely and a little more balanced. I took about three weeks. This time my feelings were much clearer. Happiness.

My supervisors and I talked about my timeline for submission. About how much time they each needed to read my penultimate draft and about how much time I needed to make corrections. Miscommunication or miscalculation, this caused me the most stress. Suffice it to say: you all need more time than you think. References will get mangled when you compile your document, other deadlines will come up and supervisors will need more time than anticipated, people will be on vacation, etc..

Most of my revisions came back to me on Saturday. I submitted on Wednesday. My final sprint was 4.5 days and I tell you, it felt like a month (or 7). Multiple times I considered postponing submission, once I thought about never submitting (I could be happy working at a burger joint, couldn’t I?) but mostly I thought about needing to just get it done. I could have kept working on it for weeks. I could still be working on it. I think I might feel like I could always still be working on it. Ultimately I didn’t have a choice – I was fortunate enough to be invited for two campus interviews and both were imminent which meant I needed to submit.

So, I submitted.

I thought I’d submit and simply feel happy. Maybe a little relief.

I felt those things but I also felt frustrated and angry and sad and anxious and proud and hopeful and giddy and silly and smart and bewildered. I was so completely overwhelmed.

But, it is submitted.

Vote Savvy

In July a few friends and I registered a project we’ve been working on as a non-profit. We are called Vote Savvy and our mission is to make politics accessible and fun. We are working on the Canadian Federal Election to be held on October 19, 2015. We’ve collected and created a bunch of great tools to help youth learn, choose and vote savvy. Take our savvy survey to get started. Next, check out some of these great resources:

Learn: Our survey is a great first step but explore even more election issues with Pollenize.

Choose: Vote Note is our favourite all access pass to the election and candidates running in your riding.

Vote Savvy: We’re injecting some youthful excitement to this election. Check out the first Vote Mob hosted by students at the University of Guelph!

You might also like our tools for organizers and blog.

I am pretty excited about the project and would be delighted if you shared our resources.

Trace Interview Workshop at #SMSociety15

This morning Devin Gaffney and I ran a workshop on trace interviews at the Social Media and Society Conference. Trace interviews involve collecting and visualizing trace data (in this case, social media data, like tweets or likes). The researcher brings visualizations into the interview setting and invites the interviewee to help interpret the data. Since the interviewee is the person who left the trace data in the first place, their insight is valuable for understanding the context of communication, the validity of data and the meaning behind traceable online interactions.

Heather Ford and I describe the strengths and weaknesses of this approach in our International Journal of Communication article.

You can also check out the slides we used for this workshop. I will add a full bibliography shortly.

This is a mixed-methods approach in development. We would love to hear your feedback, suggestions, questions and concerns. We’d also love to hear about other research using similar techniques. Feel free to comment below, tweet or email.

Here is a simple network graph which visualizes the relationships among some of our workshop attendees. Each node (circle) is an attendee. The edges (lines) represent times one attendee has mentioned the other.

New paper! Trace Interviews (in IJoC special on #qualpolcomm)

Last spring Heather Ford and I attended an ICA pre-conference on qualitative political communications researcher. The conference organizers went on to coordinate a special issue of the International Journal of Communications and invited us to contribute.

Our piece, along with the rest of the issue (which is pretty much just full of wonderful) is available free! Check it out.

Thanks so much to the incredibly hard working team of editors! Follow them: @mj_powers, @rasmus_kleis, @davekarpf and @kriessdaniel

What does privacy mean?

From Beyond Google, 2015, Dalhousie University. In Beyond Google, a third year information management course, we explored how data and information is stored, social and mobile. We started the course talking about media as an extension of the self and ended it with a look at protecting ourselves from privacy infringements.

“Private” is, as most people will define it, the opposite of “public.” Something that is private is often personal, it is for me and not for you, it is information I’ve put limits on. Though privacy is a thing we hear about on a daily basis and all seem to know about intuitively, it is not a simple concept.

When we say we want to maintain our privacy what we are really saying is we want to control information about us and about what we do. More precisely, we want to control the audience of that information. We don’t want everyone to know our health records, we want our doctor to know and our close family to know, but not the guy sitting beside us on the bus.

How much we value other people not knowing things about us is a social norm. What I mean here is that in different cultures and at different points in time people’s desire for privacy is varied. Your expectation for how much control you get over information about you and what you do is socially constructed.

You may remember Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook infamously claiming privacy is dead – the social norm no longer exists. This normative view of privacy is where he was coming from, since people are happy to give up control of their personal information now. That is what online social networking sites do. This is, of course, a huge over simplification.

While people do give up a lot of personal information online, they still don’t want the stranger next to them on the bus to know about their health issues. Even information people are willing to relinquish control over on Facebook is not necessarily information they want to have spread via other channels of communication. For example, you may be fine posting a crazy St. Patty’s day photo on Facebook but it is not exactly the ideal conversation starter around the board table at work. So privacy, as a social norm does persist.

Zuckerberg’s comments about privacy being dead are in line with a stream of thinking that says youth in particular do not know or are unaware of privacy risks online. The assumption is that since youth are regular users of social media and mobile apps which heavily rely on personal data, they do not care about their privacy. In reality, however, research has shown that youth are actually more likely than their older counterparts to check or change their privacy settings (among others, Grant Blank, Gillian Bolsover and I have argued this).

Helen Nissenbaum, a well known scholar and privacy expert, talks about privacy in context. Her work argues for that view of privacy where what we really want is to control when and where our information is shared with others. Privacy infringements can be thought of as use and sharing of information in improper settings or for unintended purposes. So, if I post my address to a closed Facebook event because I am inviting friends over and then that address is given to a company who starts sending me junk mail, that is probably going to feel like violation of privacy to me.

A lot of people talking about privacy and the Internet focus on privacy in terms of controlling how much information advertisers and marketers get or how much access governments have to citizens’ online histories. But, privacy is also more personal, it is also what the people you talk to everyday have or do not have access to.

To that point, Marwick and boyd do an excellent job of considering the implications of online spaces and privacy in context in their work on context collapse. Thinking about how privacy is contextual — In one context you are happy to share information about your new romantic interest, for example chatting with friends. In another context you would not want that information shared, say, at a family dinner where nosey relatives can all have their say. The problem is many online social networking sites cause those two contexts (and others) to overlap or collapse. Mom, uncle Bob, your childhood bff and former boss are all on Facebook. Mitigating context collapse is an issue of maintaining privacy.

And so, for a range of reasons, I want to be able to control the audience and the context. That is privacy.

by vintagedept – https://www.flickr.com/photos/vintagedept/15704560667